David Livingstone and the Blantyre Cotton Works

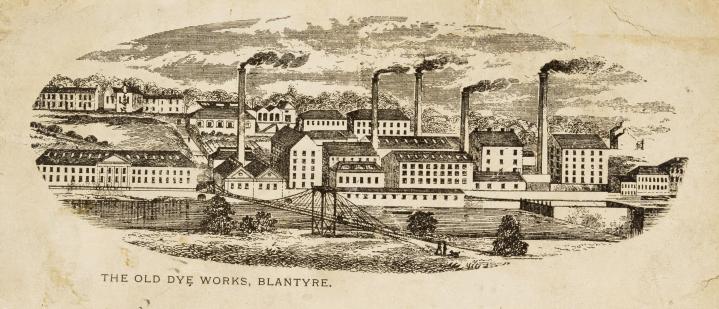

Livingstone grew up during the Industrial Revolution. This was a time when technological advances meant industry developed rapidly. Machines took over jobs that had previously been done by hand, meaning they could be done more efficiently. Thanks to innovations in machinery, the cotton industry boomed.

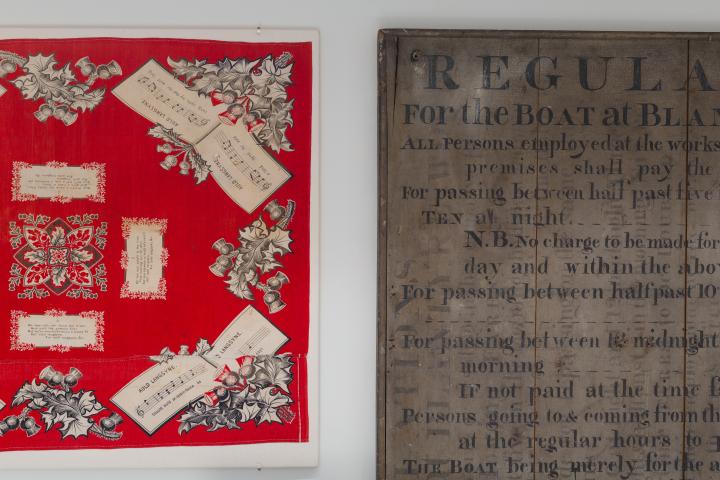

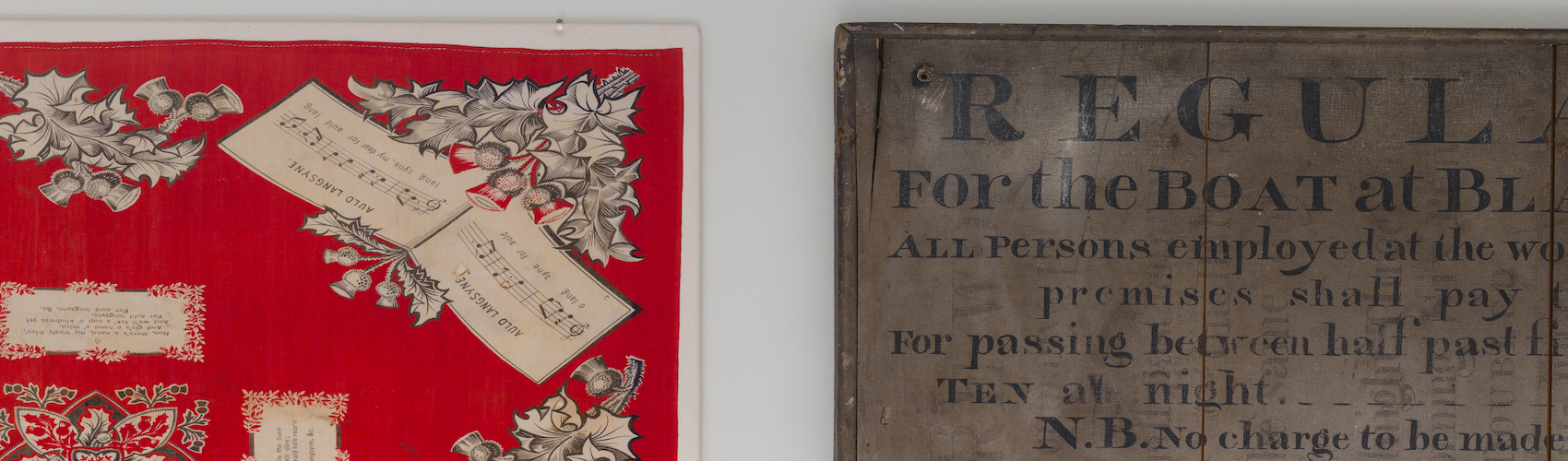

Enslaved people were forced to work on plantations in America and the Caribbean. They grew and picked raw cotton. This cotton was then shipped to countries including Scotland, where it was woven into cloth in cotton mills. The cloth was then exported around the world.

Originally from the Scottish island of Ulva, the Livingstone family moved to Blantyre in search of employment and a better life. They found work at the Blantyre Cotton Works, a cotton mill located in the Blantyre Works Village next to the River Clyde. David was born on 19 March 1813 in the mill worker’s accommodation, Shuttle Row (where our museum is now located). He lived here with his family in a single room, known as a single-end.

At the age of 10, David began working a piecer. His job involved ducking under the cotton spinning jenny machines to tie together the broken threads, with the machines moving the whole time. This was a dangerous and difficult job. The machines were so loud they could cause deafness. David worked long hours from, 6am to 8pm, After a long day at work, David went to school for a further two hours in the evening.

Surprisingly, Livingstone didn’t begrudge this hard labour, saying “Looking back now on that life of toil, I cannot but feel thankful that it formed such a material part of my early education; and, were it possible, I should like to begin life over again in the same lowly style, and to pass through the same hardy training.” David Livingstone, Missionary Travels, 1857.

When he was 19 years old, Livingstone was promoted to be a spinner in the Mill. His wages allowed him to pay for tuition at the Andersonian Institute, now part of Strathclyde University. He intended to continue working while training for his medical degree.

Unfortunately, he lost his job at the end of his first year His lack of funds meant Livingstone had to find an alternative way to finish his medical training; he was eventually accepted into the London Missionary Society (LMS).

Years later, after his initial 16 years of travel in Central and Southern Africa, Livingstone returned to Blantyre at the invitation of the Blantyre Works’ Literary and Scientific Institute on the 31 December 1856. He gave a speech in the schoolroom where he had attended classes as a child, after work each day. In that speech Livingstone spoke of the links between Blantyre and Africa, and how he had often found Glasgow stamps on bales of cotton in the while traveling in Southern and Central Africa. He saw cotton as a resource that would open up what he saw as legitimate trade between imperial Britain and Africa.

Livingstone wrote that Britain was “aiding” in “the gigantic evil” “by using and increasing the demand for cotton grown in the American South and Caribbean which was produced using the forced labour of enslaved people.

Livingstone had seen cotton growing in sub-Saharan Africa and advocated for the production of cotton grown by indigenous people to be increased so it could overtake the use of American cotton in Britain. David also aimed to set up trading stations which would allow for cotton to be traded fairly. These plans never worked out.