Discovering Objects in a Diviner’s Medical Kit

During my placement at the David Livingstone Birthplace, I spent four months researching objects from Museum’s Collection which will be included in the new "Encounters on the Continent" display. This section of the Museum will feature some of the vast array of Southern African objects in the Museum’s collection and will highlight the different cultures that Livingstone encountered on his travels.

The main focus of my research were objects previously catalogued as ‘witch doctor apparatus’. I was tasked with the goal of finding out more about them and their historical context. Through my research, I discovered that they would have formed a part of a traditional healer or diviner’s medical kits. Diviners used healing methods, which included medicine made from plants and herbs, which were passed down through generations and were practiced alongside traditional ancestral beliefs. Europeans, including missionaries, at the time struggled to comprehend, and tried to discourage, the work of traditional healers which was so different from contemporary Western medical practices.

Before I could properly begin my object research, I came across a problem that could hinder my research. ‘Witch doctor’, the main identifying term associated with the objects, led to my initial research of books, articles and journals that were predominantly written from a nineteenth century European colonial perspective. The sources frequently mentioned the term ‘witch doctor’ without expanding on the roles, nor on the use of medicine kits or the objects that I was researching. Furthermore, the term is now considered offensive to many indigenous beliefs and practices, and has negative connotations that do not correctly explain these practices.

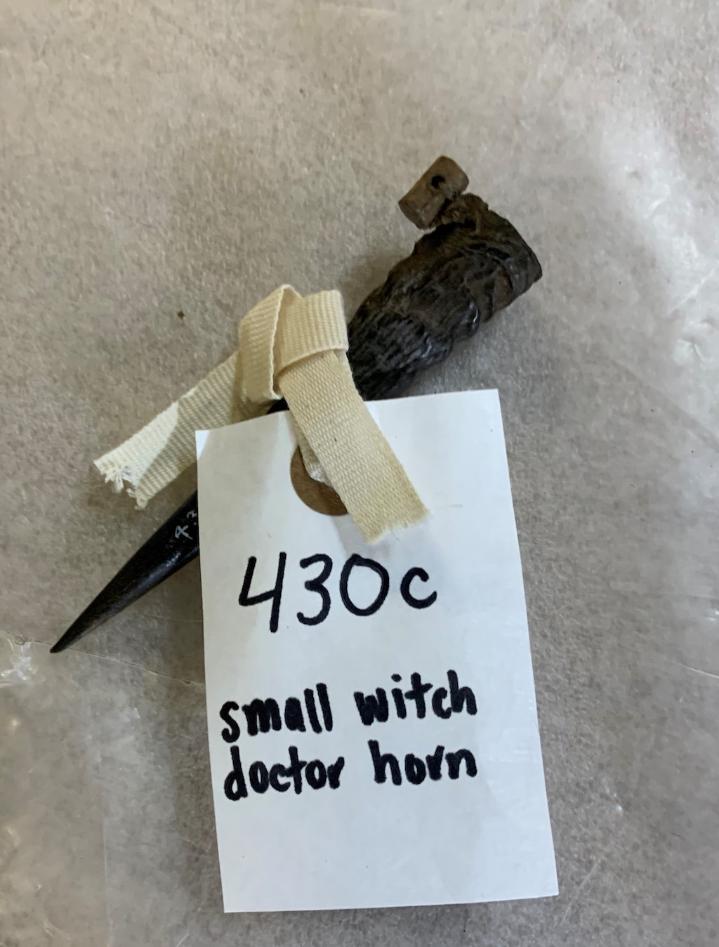

Slightly perturbed at not being able to find any information on the objects in question, I turned to experts in the field for advice about the correct terminology that I should use, which would enable me to properly start my research. This decision proved to be advantageous, and I discovered that ‘traditional healer’ and ‘diviner’ were common terms used today in lieu of ‘witch doctor’. With the correct terminology, I carried on researching and unearthed some fascinating information. The object previously labelled as a ‘small witch doctor horn’, for instance, turned out to be a small antelope horn. Antelope horns had many uses within Southern African diviner medical practices. Traditional healers of the Zulu community, for example, hung them around their necks to carry medicines. It is possible, that this horn formed part of a diviner’s medical kit, alongside the other objects I was researching. Similarly, two wooden carvings, previously labelled as ‘human carvings’, would also have formed a part of this medical kit. They are likely ancestor twin votives and the bent knees depicted are surprisingly significant. My research identified that bent knees in sculptures carved by the Kongo people are representative of living beings , which is important when considering that these figures may have been used as some form of charm in the traditional healer’s kit, perhaps inferring a symbolic function.

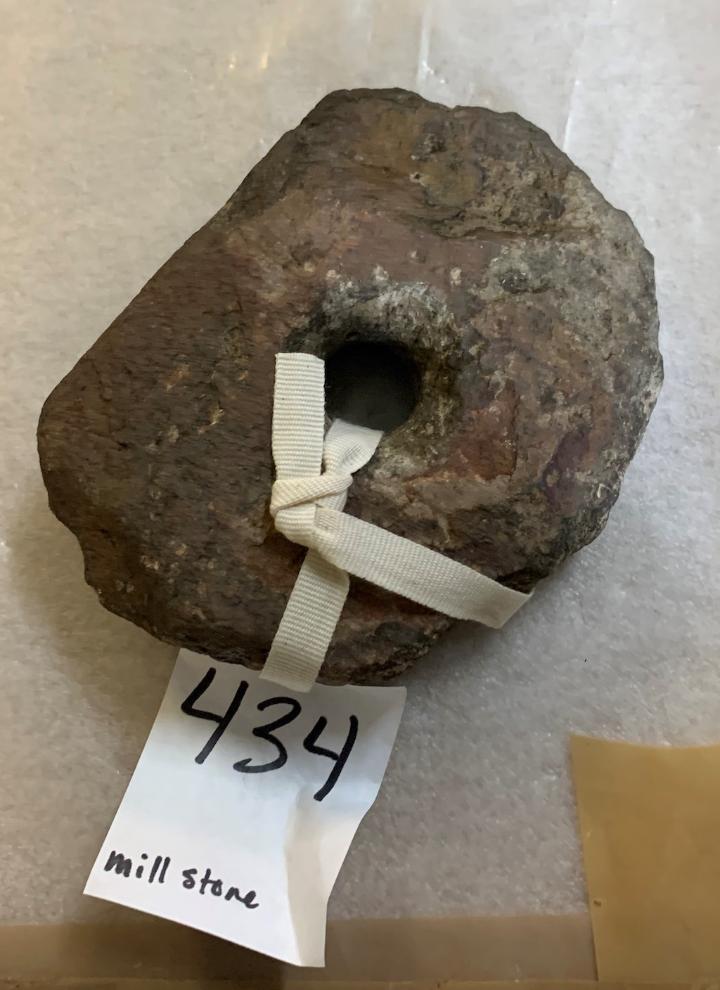

The last object that I researched was originally labelled as a ‘mill stone’. Without any context, this stone may appear to serve the simple utilitarian purpose of grinding grain. However, it became apparent through my research that it was in fact a bored stone that may have served many spiritual functions. For example, medicine was poured through the hole in the stone by the traditional healer of the Transvaal Bantu people as part of their practice. In traditional African San Shamanism practices, beating the ground with the stone allowed for a channel of communication to open up between community Sorceresses and their ancestors. Discovering this information was a real “Eureka!” moment for me, and I was surprised to discover that such a simple object had so many interesting and intriguing functions within different communities.

I thoroughly enjoyed my placement at the DLB and it was fascinating to learn more about these objects and their histories. I am pleased to say that I managed to break through the brick wall I faced at the beginning of my placement due to my perseverance and determination to complete my research.

All in all, my time at the David Livingstone Birthplace has been educational, insightful and very rewarding. I’ve learnt a lot, not just about these objects, but also about the importance of collaborative working, using correct terminology, and day-to-day museum practices. I hope you find these objects as interesting as I do, and I can’t wait to see them on display, alongside my research, in the Museum when it opens!

I would like to say a special thanks to all the team at the Museum for being so welcoming and supportive of my research during my placement. Thank you also to Patricia Allan (Glasgow Museums), Lawrence Dritsas (the University of Edinburgh), Sarah Worden (National Museums Scotland), Sue Giles (Bristol Museums) and Lisa Graves (Bristol Museum and Art Gallery) for their help with my research.

References

[1] Ethel E. Thompson, ‘Primitive African Medical Lore and Witchcraft*’ Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 53:1, 80-94 (1965) p.83.

[2] Wyatt MacGaffey, ‘Fetishism Revisited: Kongo “Nkisi” in Sociological Perspective’ Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 47:2, (1977) p.175.

[3] Raymond A. Dart, ‘The Ritual Employment of Bored Stones by Transvaal Bantu Tribes’ The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 3:11, (1948) p.63.

[4] M. Lombard, ‘Bored Stones, Lithic Rings and the Concept of Holes in San Shamanism’ Anthropology Southern Africa, 25:1&2, (2002) p.23.

About The Author: Aimee Murphy

I am a MSc student studying Art History: Collecting and Provenance in an International Context at the University of Glasgow and a current work placement student at David Livingstone Birthplace Museum. Prior to this, I completed a BA in Art History at Goldsmiths, University of London, and spent 5 years independently curating contemporary art exhibitions. Aside for my love of contemporary art, I am interested in the decolonisation of museums and making museums and galleries more transparent, particularly through the display and enhancement of provenance information.

Further Reading

Cadbury, Tabitha. ‘A Trader in Central Africa: The Dennett Collection at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter’. Journal of Museum Ethnography 20 (2008) accessed 18/04/2020 https://www.jstor.org/stable/40793874

Dart, Raymond A. ‘The Ritual Employment of Bored Stones by Transvaal Bantu Tribes’ The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 3:11, (1948). accessed 18/04/2020 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3886952

Dorsey, George A. ‘The Ocimbanda, or Witch-Doctor of the Ovimbundu of Portuguese Southwest Africa’ The Journal of American Folklore 12:46 (1899) accessed 18/04/2020 https://www.jstor.org/stable/534176

Hokkanen, Markku. ‘Scottish Missionaries and African Healers: Perceptions and Relations in the Livingstonia Mission, 1875-1930’. Journal of Religion in Africa, 43:3 (2004). accessed 18/04/2020 www.jstor.org/stable/1581549

MacGaffey, Wyatt. ‘Fetishism Revisited: Kongo “Nkisi” in Sociological Perspective’ Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 47:2, (1977). accessed 18/04/2020 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1158736

Lombard, M. ‘Bored Stones, Lithic Rings and the Concept of Holes in San Shamanism’ Anthropology Southern Africa, 25:1&2, (2002). accessed 18/04/2020 Link

Shapera, Isaac. A Handbook of Tswana Law and Custom. London: Oxford University Press, 1955.

Stanley, B. 'The Missionary and the Rainmaker: David Livingstone, the Bakwena, and the Nature of Medicine', Social Sciences and Missions, 27:2-3, (2014) accessed 18/04/2020 https://doi.org/10.1163/18748945-02702003

Thompson, Ethel E. ‘Primitive African Medical Lore and Witchcraft*’ Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 53:1, 80-94 (1965). accessed 18/04/2020 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC198231/