The Smoke That Thunders

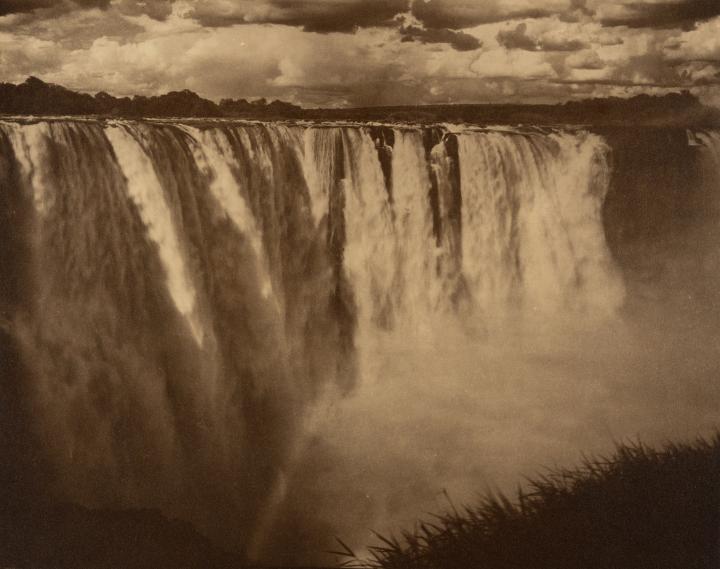

Located on the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe, Mosi-oa-tunya ‘the smoke that thunders’ (Victoria Falls) is classed as the largest waterfall in the world. At 1,708 metres wide and 108 metres tall, it is twice the height of Niagara Falls. The spray from Mosi-oa-tunya can be seen over 18 miles away.

Livingstone heard about the Falls before saw, hearing reports from the people he met in Africa. Sebetwane, the leader of the Makololo people met Livingstone in 1851 and asked him, "have you smoke that sounds in your country?"

Livingstone finally reached the Falls on the 16th November 1855. He was accompanied by Sekeletu, the son of Sebetwane who had recently become chief of the Makololo at 18 years old following his father’s death. Sekeletu, as Livingstone recalled, was exceptionally kind to him; feeding Livingstone’s travelling party which numbered 200 men. Sekeletu also provided them with 12 oxen as well as hoes and beads to trade for a canoe.

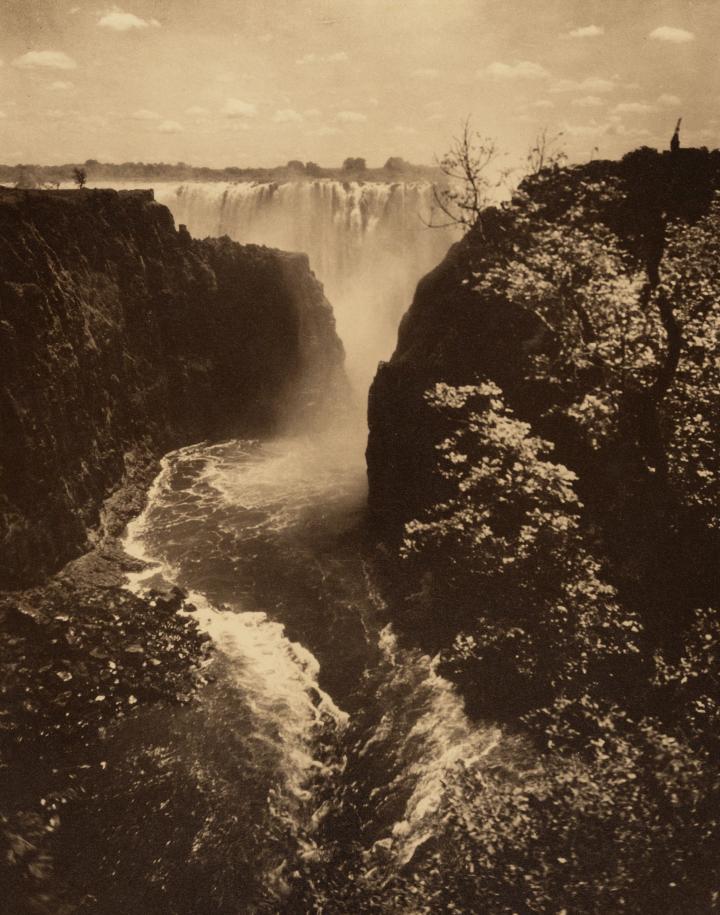

Livingstone depended on the experience of his travelling companions to navigate the dangerous waters leading to the Falls. He wrote, “I left the canoe by which we had come down thus far, and embarked in a lighter one, with men well acquainted with the rapids, who, by passing down the centre of the stream in the eddies and still places caused by many jutting rocks, brought me to an island situated in the middle of the river, and on the edge of the lip over which the water roars. At one time we seemed to be going right to the gulph, but though I felt a little tremor I said nothing, believing I could face a difficulty as well as my guides.”

On the island mentioned, Livingstone cut his initials and he date into the bark of a tree recording in his journal this was “the only time I have been guilty of this act of vandalism”. The Museum has a cast of this carving in its collection. Livingstone further left his mark by planting seeds of peaches and other fruit. He thought the spray of the Falls would help the plants flourish but upon his return in 1860, Livingstone was dismayed to find the poor saplings had been trampled by hippopotami.

Documenting the scale of the Falls, Livingstone compared it to the Thames and the flooded Clyde at Stonebyres waterfall in Scotland but Livingstone would later conclude it “is a hopeless task to endeavour to convey an idea of it in words.”

He said of the Falls: “The whole scene was extremely beautiful; the banks and islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great variety of colour and form…no one can imagine the beauty of the view from any thing witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.”

Livingstone noted that the ancient name of the Falls was Shongwe before the arrival of the Makololo people in the area in the first half of the 19th century. According to some sources, the name Shongwe was a reference to the rainbow visible in the spray but others claim it refers water at the bottom of the Falls’ resemblance to a boiling pot. It was the Makololo who named the Falls Mosi-oa-tunya. This name was also adopted by the Lozi people, and is still used by them today.

When renaming it the ‘Victoria Falls’ after the British monarch, Livingstone stated that he was using the “same liberty as the Makololo”. Victoria Falls became the official name, but it is still commonly referred to as Mosi-oa-tunya throughout Zambia, and in parts of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe’s ruling party at the time, the Zanu PF party, had been campaigning to officially change the name back to Mosi-oa-tunya since 2013.

Despite Portuguese records and French maps from the 17th and 18th centuries showing near accurate notation of the (partial) routes of the Nile and the Zambezi, the popular idea in Europe was that Africa’s interior was a vast desert. This article from The Guardian provides hundreds of years’ worth of European maps showing how little of Central and Southern Africa was documented. This was the case until Livingstone embarked on his cross-continental journeys to find where the Zambezi river fed into the Indian Ocean.

While European knowledge about Southern African landmarks was lacking, there is evidence from the area around the falls of permanent settlements dating from the late 7th century.

This excellently researched blog gives an in-depth history of the people of this area.

Although we strive to be fair and accurate, we welcome any corrections or additional information that you may want to provide for us, please get in touch by leaving a comment or sending us an email info@dltrust.uk .

Sources

Missionary Travels and researches in South Africa by David Livingstone, 1857.

Narrative of an expedition to the Zambesi and its tributaries and of the discovery of the lakes Shirwa and Nyassa 1858-1864 by David and Charles Livingstone 1865.

Livingstone’s African Journal 1853-56 edited by I. Shapera vol. 2, 1963.